Morteza Falah-Delavar’s Execution; Denied Army Exemption Despite Schizophrenia Diagnosis

Iran Human Rights (IHRNGO); August 2, 2022: Following official news of the execution of a conscript last week, his identity has been established as Morteza Falah-Delavar who was medically unfit to serve due to severe mental illness that was ignored by relevant authorities.

According to new information obtained by Iran Human Rights, 28-year-old Morteza Falah-Delavar who was executed in Rasht Central Prison on July 28 was unfit to serve in the army due to his schizophrenia which was exacerbated by his conscription. Despite all efforts by his family, the evidence was ignored by authorities. Morteza was executed just 13 months after being arrested for the murder of his superior.

Official sources had reported Morteza’s execution for the murder of Omid Chayi, his superior, without naming him or details of his case. Local websites had previously reported that the victim was in charge of the Lahijan Province Public Service Department and repeatedly denied the executed man’s request for an exemption from service.

A source close to Morteza Falah-Delavar explained Morteza’s upbringing: “Morteza was born in a religious family of four from a lower middle class background and had an older brother. His mother is a housewife and his father worked in a private company before retirement. Morteza had a stutter which prevented him from being able to communicate with the world around him. He had trouble at school and shied away from other children. As he grew older, these issues grew to the point that he became a recluse that stayed at home and had no social life. He also used to speak to himself, had terrible internal rage due to his stutter and being unable to interact when people spoke to him and bipolar disorder.”

“Morteza’s family made no efforts in treatment when he was growing up until his symptoms became so severe between 22-28 years of age that they were forced to take him to a psychologist. There were hand written suicide notes and his family found a rope in his room that he was going to use to kill himself. Morteza was under treatment at Dr Ayouzi and Dr Nadi’s specialist clinic in Lahijan for a few years,” the source added.

As men above the age of 18 are required to serve 24 months of compulsory military service in Iran unless they qualify for an exemption, Morteza was conscripted. The source explains the run up to his service: “As the time drew closer for him to leave, Morteza became more terrified of what he imagined it would be like and his anxiety and psychosis became worse. His family began the application to apply for an exemption due to his mental illness. His case went to the police station in Lahijan city. After submitting the documents, the initial ruling was that he would be exempt from combat. Morteza’s father and the victim who was in charge of the conscripts, filed an appeal and the case was referred to the Navy Hospital (Medical Commission) for further investigation. After interviewing Morteza and his family, doctors at the Navy Hospital verbally told them that his condition was extremely acute and could cause many dangers. However, they still decided to form the Medical Commission and as the decision makers, Ms Zarabi and Dr Najafi should have exempted Morteza on the army’s explicit orders and placed him under the care of social welfare and therapy. Instead, they ignored the orders and referred him to a mental health hospital for further examination. The hospital refused to admit him due to a lack of beds. None of the administrative work was carried out by Morteza at any stage but his family members.”

Describing the day of the murder, the source said: “During that time, one day when none of the other members of his family were home, Morteza took two knives from the kitchen, hid them in his clothes and set off for the police station. Unfortunately, security didn’t perform their jobs properly and he went through to the victim’s room. Ordinarily, the victim who was a lieutenant should’ve been accompanied by a soldier but he was alone that day. Morteza entered the room and stabbed the lieutenant.”

“Once the news spread at a political level, Morteza, his family and anyone related to the case were dealt with severely. All their phones were tapped and each family member was subjected to intense interrogations. The family were also struggling to secure him a lawyer. Most lawyers refused to accept his case and those that did, would end up excusing themselves from the case due to external pressure. The victim’s family also refused to see or speak to Morteza’s family and insisted on his execution until the last day. In the meantime, the authorities’ propaganda machine banned any reports on the case in order to cover up the root causes of the incident, compulsory military service and that he was denied a medical exemption due to the Medical Commission’s mistakes. On the other hand, the Forensic Medical Organisation which had confirmed Morteza’s diagnosis changed its opinion and ruled that Morteza was mentally fit. The judge was also overheard telling Morteza’s lawyer that it was out of his hands and he was under orders to sentence him to execution. His family even tried to delay his execution by appealing to religious authority that his execution would be religiously wrong but to no avail. Morteza was executed in Rasht Central Prison just 13 months after the incident took place. And the official report was that a lieutenant was killed by a conscript who didn’t want to do military service without even mentioning his mental illness and how his family had tried to obtain an exemption.”

Article 149 of Chapter Two of the Islamic Penal Code (2013) which relates to the lack of criminal responsibility states: “If the perpetrator has a mental disorder at the time of committing the crime that they lack willpower or judgement, they are considered insane and are not criminally responsible.”

While obtaining document evidence of medical diagnosis are difficult due to a lack of transparency, Iran Human Rights has reported many cases of people suffering from mental disorders being executed throughout the years. Another recent confirmed case was that of Mohsen Safari who was executed in Isfahan Central Prison on July 13 for drug-related charges despite confirmation from the Forensic Medical Organisation that he was suffering from bipolar mental disorder.

In carrying out such executions, the Islamic Republic of Iran is breaching both its own laws and its international obligations. In an adopted resolution by the United Nations High Commission, it urged States “not to impose the death penalty on a person suffering from any form of mental disorder or to execute any such person.”

Those charged with the umbrella term of “intentional murder” are sentenced to qisas (retribution-in-kind) regardless of intent or circumstances due to a lack of grading in law. Once a defendant has been convicted, the victim’s family are required to choose between death as retribution, diya (blood money) or forgiveness.

According to reports compiled by Iran Human Rights, at least 126 people were executed on drug-related charges in 2021, a fivefold increase compared to drug executions in the previous three years. This trend has continued into 2022, with 91 executions recorded in the first six months of 2022, double the number for the same period in 2021 when 40 people were executed.

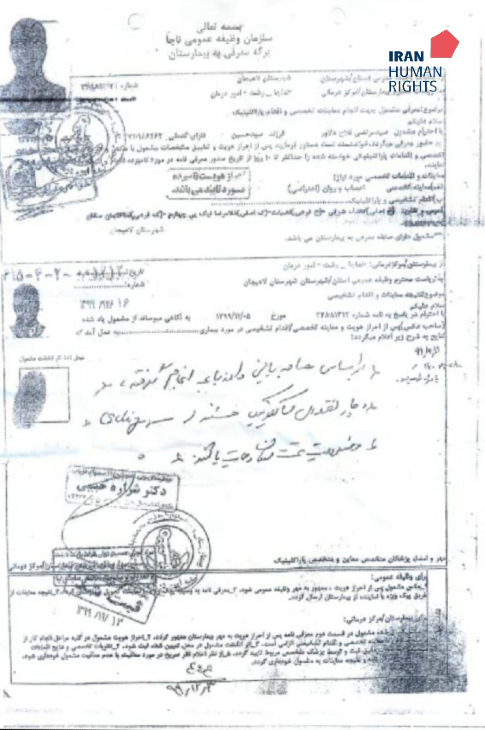

Morteza Falah-Delavar's medical diagnosis of psychosis caused by schizophrenia:

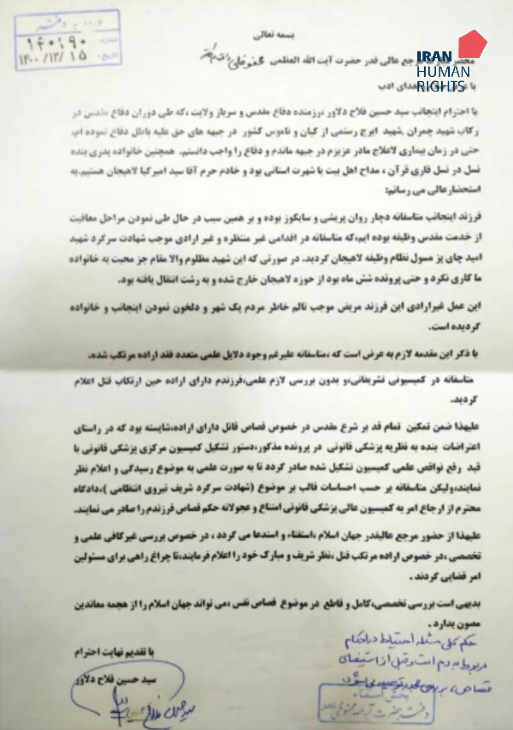

A letter sent by Morteza's family:

Morteza's death notice: